‘Coercive control’ gaining recognition

12 August 2022Read the research paper

Coercive control’ has risen in prominence as an issue in Australian society in recent years, particularly following the 2020 murder of Queensland woman Hannah Clarke and her three children at the hands of her estranged husband.

A research paper from the Victorian Parliamentary Library, 'What is coercive control?', explores the definition, prevalence, legislative frameworks and the arguments for and against criminalisation.

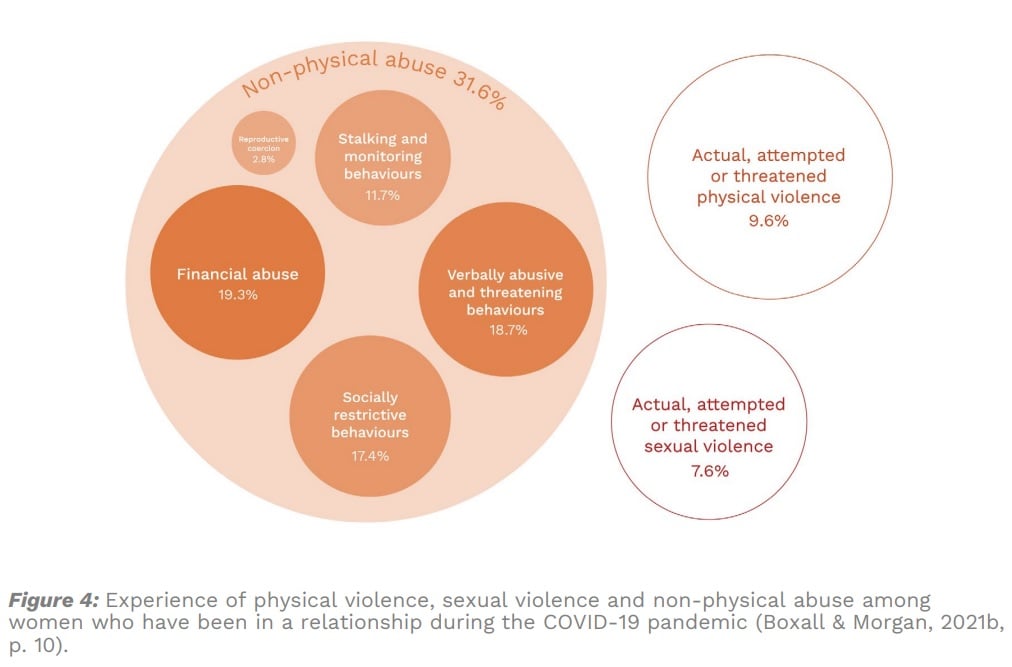

‘Coercive control’ describes a systematic pattern of behaviour used by a person to dominate and control another person, usually an intimate partner. It is almost exclusively perpetrated by men against women and includes emotional and financial abuse, stalking and intimidation.

In November 2021 the Victorian Legislative Council agreed to a motion recognising the ‘prevalence of coercive control in family violence offending’ and calling on the government to look into ways to ‘enhance the understanding of coercive and controlling behaviour in our community and the justice system’.

Currently Tasmania is the only jurisdiction to have criminalised types of coercive behaviour.

Most Australian states and territories do recognise coercive control as abuse and address it through relevant orders and notices under civil law.

However, some suggest that coercive control should specifically be criminalised as is the case in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Supporters of this approach argue criminalisation provides greater access to protection and justice for victim-survivors, and shows the behaviour is damaging and unacceptable. A coalition of groups from the sector have called for the criminalisation of coercive control accompanied by a guarantee of sufficient resources being made available to the judicial and policing sectors.

Those opposed believe that civil law better addresses the socio-legal complexities, and highlight the disproportionate impact of criminalisation on First Nations peoples. Some, such as the Women’s Legal Service Victoria, argue that international evidence does not support criminalising coercive control, suggesting it does little to contribute to victim-survivor safety.

A separate paper, Intersectional Complexities of Coercive Control, has also been published by the Parliamentary Library.

Coercive control encompasses a wide range of behaviours and is experienced in varied ways by different population groups such as women with disabilities, women living in rural areas or migrant women.

Unlike other groups of women subject to coercive control, migrant women, for example, may be subject to threats to withdraw sponsorship, cancel their visa or to send their children to another country.

Any policy response needs to take into account the particular circumstances of each group. Women with disabilities, for example, are proportionally more likely to experience emotional abuse. This abuse takes a form unique to their circumstances such as withholding of or forcing medication or withholding of essential assistance with personal tasks.

The paper reviews the literature in relation to women with disabilities, as well as culturally and linguistically diverse women, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, women living in rural, regional and remote areas, and LGBTIQA+ people.

For each group the paper considers the prevalence of coercive control, particular experiences and the barriers to seeking support.